by Dori DeCamillis

The following paintings make up a series of panels I completed between 2006 and 2011. They are painted with oils on board and copper with handmade ceramic tile.

I moved to Alabama 18 years ago, amazed by the historical and natural wonders that are largely overlooked by Alabamians. I received the Alabama State Council on the Arts Individual Artists Fellowship for 2006-07 which inspired a series of 12 large paintings in my mixed-media panel format based on some of my favorite Alabama places.

In most cases I worked with a handful of extremely dedicated people who have devoted their lives to saving, managing, and promoting awareness of their place. The series was featured in a solo exhibit of the work titled "Prominence of Place" from April to September of 2011 at the Mobile Museum of Art.

A printed book about the project, "Exhibit A, Paintings of Alabama Places" is available at blurb.com Here is the intro to the book, explaining more about the story behind the project.

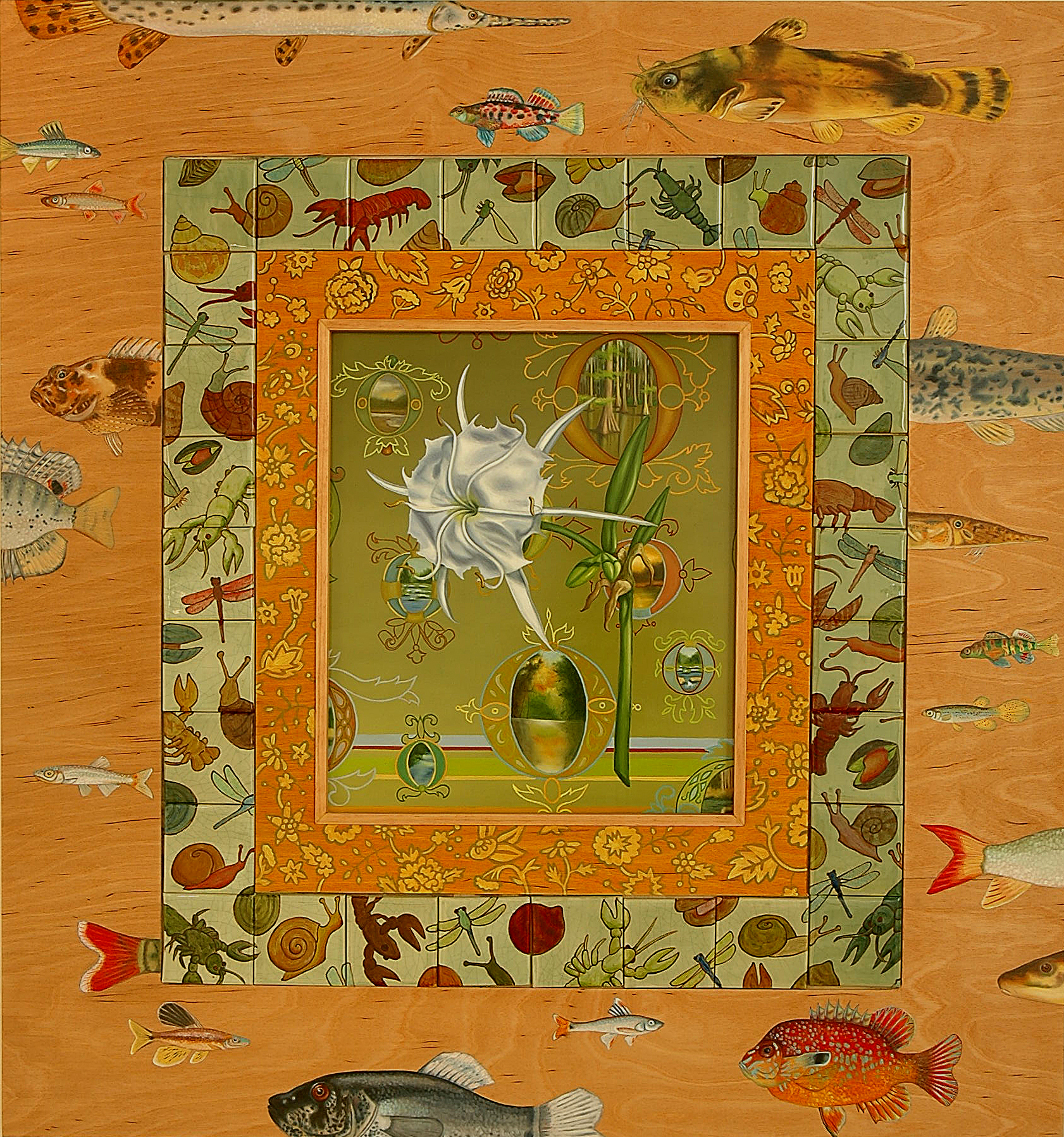

2007, 48” x 45” SOLD

Best in Shoals: The Cahaba River

I was most surprised on my Cahaba River canoe trips by the amazing amount of wildlife in and around the river. Every time Randy Haddock, the Cahaba River Society’s biologist, dipped a net into the water to show us river creatures, he pulled out an abundance of various snails, mussels, fish, and crawfish. Shiny, colorful dragonflies and damselflies darted around us all day. Each stop along the shoals became a treasure hunt for one of the many rare species of river fauna.

My astonishment is corroborated by statistics; the Cahaba contains more fish species per mile than any other river in North America. The river also holds the most snail and mussel species in the world. Rare plant life abounds as well; the shoals and glades host a variety of uncommon and endangered plant species, including the Cahaba Lilly, depicted at the center of my painting.

Unfortunately, the Cahaba River is also considered to be one of the top ten most endangered rivers in North America. Problems such as urbanization, soil erosion from forest clear-cutting, pesticide run-off from agriculture, and toxin discharge from mining and industry threaten aquatic life and affect one of the largest supplies of drinking water in the state. Birmingham receives over half its water supply from the Cahaba.

Organizations such as the Cahaba River Society are working to protect the Cahaba. Go to www.cahabariversociety.org for more information.

2007, 42" x 48"

Southern Belle: The

Alabama Theatre

The Alabama Theatre was the original inspiration for my current painting format. I marveled at its lavishness, and soon after began using elaborate, architectural-inspired ornamentation not to decorate my work, but as the subject. When I walk into a cathedral, or a place like the Alabama, I imagine the artists who created it, the time they spent, the care they put into their craft. The magnitude of scale and intricacy of detail are a visual banquet, and a testimony of loving dedication to the meditative, slow, and time-honored tradition of being an artisan and manual craftsman.

Brought together in 1926, the leading theater architects of the day and artists from all over the world designed and constructed the Alabama—the biggest and most elaborate movie palace in the South. The fabulously opulent interior has stunned the imagination of visitors ever since it opened.

For 54 years the Alabama entertained the community with Hollywood feature films often preceded by an organ show played on the largest Wurlitzer organ in the South, a newsreel, cartoons, movie previews, and sometimes a vaudeville show. As the years passed and businesses moved to the suburbs, theatre attendance declined, and in 1981 the Alabama bankrupted and closed its doors.

A small group of citizens dedicated to reviving the theater formed a non-profit organization and re-opened the theatre in 1987. Birmingham Landmarks, Inc. now hosts public and private events and receptions, classic films, concerts, film festivals, and the opera and symphony. With over 250 events annually, the Alabama entertains over 500,000 people each year.

The Alabama Theatre for the Performing Arts is financially maintained by events held there and by public contributions. For more information go to www.alabamatheatre.com.

2009, 45” x 48”

Safe Harbor: Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge

Located on the Fort Morgan Peninsula of Alabama’s Gulf Coast, Bon Secour consists of 7,000 acres of protected beach and pine-oak woodlands, some of the state’s last remaining undisturbed coastal wildlife habitat. This relatively small area preserves dunes, marshes, wetlands, scrub and old forest habitats crucial to the survival of many animal species.

The tiles on my piece represent the animals, some endangered, found in Bon Secour either permanently or temporarily. Each spring and fall migratory birds can be sighted as they fly though toward their seasonal destinations. Summer brings nesting sea turtles and osprey, while October hosts the migration of Monarch butterflies. The endangered Beach Mouse makes a permanent home at Bon Secour, and feeds on the local sea oats, pictured in the center of my piece.

The botanicals around the outside of the panel were painted from photos from an October trail hike, when many wildflowers were in bloom, and the shells around the centerpiece were all collected previously from the beach near there. I felt it important to use plenty of white in this work, inspired by the sand, the light, and the reflections of the water.

Bon Secour is maintained by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and can be reached at bonsecour.fws.gov.

2009, 45” x 48” SOLD

Gay Wah Nesah: Stonetalker’s Wall

Tom Hendrix began constructing a stone wall decades ago on his property 15 miles north of Florence, Alabama. His intention was to build a monument to his great great grandmother, a member of the Yuchi Indian Tribe, who was sent on the Trail of Tears. Once she arrived in Oklahoma, she escaped, and walked back all by herself to her home waters on the Tennessee River in Alabama. It took her five years, and she is the only person known to have done it. Her amazing story was passed on to Tom through his grandmother, and inspired his colossal undertaking, a winding rock wall that rivals any environmental project done by a single person.

Little known to most Alabamians, Tom Hendrix’s wall is known to people all over the world, especially in the spiritual community. The heartbreaking and uplifting nature of its inspiration, and the knowledge that one man dedicated himself to such an enormous task, offers a powerful, indescribable experience when visiting the wall. People of many faiths and nationalities come to the wall to experience that which can only be felt by going there. Describing the wall or showing images of it conveys little of what is important and amazing about it. One must visit it to understand why people say, “You just have to go there.” Gay Wah Nesah means “a spiritual place.”

Rocks sent from people all over the world have been incorporated into Tom’s wall, including rocks from the top of Mount Everest, the bottom of the ocean, from the Arctic and the Antarctic, from space and from the mines of South Africa. People give stones they have cherished their whole lives, and many of the rocks have incredible andmoving stories that accompany them. I have depicted some of those stones on the outside layer of my painting.

The “tiles” of this piece are not real stones, but are made from clay. The next layer represents a segment of the wall where naturally formed rocks with holes form an eerie spectacle. And finally, in the center I brought in patterns from the Yuchi tribe in the background, and used the Red Root plant, or New Jersey Tea Plant, as the centerpiece—the sacred plant of the Yuchis.

Before my Exhibit A project I’d not heard of the wall or Stonetalker (Tom’s Indian name, given to him when the Yuchi tribe adopted him.) My work on this piece started a friendship with a gentle and genuine man that exemplifies the best of the benefits this project has offered me. I spent afternoons at the wall just sitting, spellbound, listening to the wisdom, humility, and humor of someone I’ve come to refer to as my idol. I’ve seen a lot of art in my lifetime as a painter, and Tom’s self-less work rates high among my favorites, although he blushes to hear himself called an artist.

2009, 45” x 48”

Pitch Black: Limrock Blowing Cave

I was guided on a cave adventure in north Alabama by Bill Finch of the Nature Conservancy, and quickly found that caves are not for sissies. I had a terrific time, but had to face utter darkness, creeping creatures, and bunches of bats. I came away with memories of a rich experience, and some stories that became funnier the farther I was from the cave. I darted my flashlight around constantly to make sure no monsters were coming at me, a bat flew in my face (which they supposedly never do), and I had to wade my way down an underground river, hunched over to avoid the ceiling, which was covered in thousands of blind, albino cave crickets.

Alabama, particularly the northern part, has one of the highest concentrations of caves found anywhere in the world. Deep deposits of limestone lie beneath north Alabama, and caves are formed when flowing water dissolves the limestone and forms tunnels. This area of cave formations stretches into Tennessee and Georgia and is called the TAG region by cavers. In Alabama alone there are over 4,100 caves.

It took many months of creative pondering to find a way to convey my impression of the cave, because the most defining feature, total darkness, has a serious lack of visuals. Everything we saw on our trip was by flashlight, and ultimately became the inspiration for the outside layer. The cave wildlife is highlighted as if in a spotlight, lending long, spooky shadows that communicate well how they made me feel. Most of the creatures portrayed in the piece are albino and blind, having no use for sight or pigment in the dark. Because caves are a unique and limited habitat, most of these creatures are rare or endangered. Alabama caves are habitat to two species of endangered bats, the Gray and Indiana bat. One cave in Lauderdale County contains the endangered Alabama cavefish that is found nowhere else in the world. It is one of the rarest of all vertebrate species.

For the tiles, I wanted to illustrate the fantastic flight patterns of the bats, which were darting around us constantly in the cave. I love bats, and my carvings ended up looking sort of cute, which pleased me. No light means no plants, and I struggled to come up with my usual botanical for the centerpiece of my painting. My solution was to show the Trailing Wakerobin, or Trillium Decumbens, a lovely and rare local flower, outside a cave entrance.

The National Speleological Society, headquartered in Huntsville, Alabama, is dedicated to the purpose of advancing the study, conservation, exploration, and knowledge of caves. The NSS also contains groups who specialize in cave rescue and cave conservation, and can be found at www.caves.org. Limrock Blowing Cave is owned by the Southeastern Cave Conservancy, another excellent cave organization. For more Info check out www.SCCI.org.

2007, 41” x 48”

Italwas: Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

In 2006 I was commissioned to paint a historically accurate painting of a Creek Indian village. In researching the subject I found that much of Creek cultural artifacts have been lost, due to the shameful Trail of Tears. With a lot of help from Miriam Fowler (who put together the life-size Creek village at the Birmingham Museum of Art) I gathered the information I needed and found images of Creek patterns in rather obscure places. I delivered the painting nine months after the piece was commissioned, and felt like I lived in the little village I’d painted.

Because of my familiarity with the Creek culture, it was a natural choice of subject for one of my depictions of Alabama places. I knew immediately that my portrayal would include the Creeks’ wonderful patterns, which I only got to use on a small scale in the village painting. I chose Horseshoe Bend as the place to represent the Creek culture because it is the most accessible site designated to observance of Creek culture in the state.

Horseshoe Bend National Military Park commemorates the end of the Creek Indian War, when, in 1814, General Andrew Jackson defeated 1,000 Upper Creeks led by Chief Menawa. The battle took place on the lands around and between a sharp bend in the Tallapoosa River in central Alabama. After the war, Creek lands that covered three-fifths of Alabama were added to the United States and opened to white settlers, and the Indians were sent on the Trail of Tears to reservations in Oklahoma. My painting is meant to commemorate the Creeks and their culture.

I chose Creek patterns taken from their beadwork, pipes, clay vessels, and blankets. My intention was not to translate Creek symbolism inherent in the patterns. I took actual patterns from artifacts found in the Southeast, and put them together in my signature style, with more concern for depicting a kaleidoscope of visual harmony than for conceptual symbolic accuracy. I fear I may have stated something goofy in Creek language, but hopefully nothing too offensive.

Horseshoe Bend National Military Park is maintained by the National Park Service, a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior. For more information, go to www.nps.gov.

2009, 45" x 48" SOLD

Fall Out: Dauphin Island Bird Sanctuary

Dauphin Island, a 14 mile-long barrier island just west of Mobile Bay, has been sited as one of the ten most globally important sites for bird migrations. One of the featured attractions of the Alabama Coastal Birding Trail, Dauphin Island Bird Sanctuary includes 164 acres with the widest possible range of habitats on the island: a fresh water lake, Gulf beaches and dunes, swamp, maritime forest, and hardwood clearings.

Bird watchers come to Dauphin Island from all over the United States and abroad to view the spring and fall bird migrations. The island is the first landfall for many of the neo-tropical migrant birds after their long flight across the Gulf from Central and South America each spring. Here these birds, often exhausted and weakened from severe weather during the long flight, find their first food and shelter. It is also their final feeding and resting place before their return flight each fall. The name “Fall-out” is a term coined to describe the phenomenon that occurs during spring migration if the migrating birds encounter relentless weather over the Gulf, and are entirely depleted by landfall. They literally fall out of the sky.

A part of my research for this piece included participation in a bird-banding with the Hummer Bird Study Group, a non-profit organization dedicated to studying and recording migratory bird populations. Dauphin Island and neighboring Fort Morgan were teeming with bird-watchers from all over the U.S. and Canada. I spent the day watching bird experts catching various birds in very large nets stretched through the woods, then weighing, measuring, and banding them. Many of the bird depictions in my painting are drawn from photographs taken while bird watcher volunteers held the little subjects before setting them free with their newly banded feet. The banded birds, if found later during other banding sessions, teach researchers about bird populations, their whereabouts, etc.

I chose the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird as the subject for the center because its migration story most fascinated me. The tiny hummers fly alone, over 600 miles of ocean in all kinds of weather twice each year. My bird is feasting on the Alabama Crimson (or Coral) Honeysuckle, a native plant and a favorite of the hummingbirds. The birds depicted on the tiles are common to the Dauphin Island Bird Sanctuary, and around the outside are birds I photographed at the banding. Botanical patterns on the piece represent some the various plants found in Dauphin Island Bird Sanctuary.

Dauphin Island Bird Sanctuary is managed by the Dauphin Island Parks and Beach Board. The Hummer Bird Study Group is a non-profit organization which travels the United States banding birds to keep track of their populations and health.

2008, 43" x 48"

Falling Awake: Sipsey Wilderness

The Sipsey Wilderness area is one of only two designated wilderness areas in the state of Alabama, and is the third largest East of the Mississippi River. Its topography is formed by the Warrior Mountains, the western terminus of the Appalachians. Numerous streams have eroded this part of the Cumberland Plateau forming lush canyons and wooded ridges. There are over 400 miles of canyons in this small area. Rocky bluffs from 50 to 200 feet in height drop away from the ridges. Some of the coves are so rugged that they have never been logged and are home to virgin and old growth trees. Sometimes called “land of a thousand waterfalls,” Sipsey hosts large cascades from 35 to 70 feet as well as hundreds of smaller ones.

As evidenced in my piece, my every visit to Sipsey has been in the fall (with no complaints from me.) I included imagery of many of the trees and plant-life, all drawn from brilliantly colored photos of my hikes. The two trees that stood out to me as being unusually prevalent were the evergreen Eastern Hemlock and the Big-Leaf Magnolia. Even with my complicated format, I found I could not include every visual aspect of the place, and so left out the rock outcroppings, dark canyons, and rushing creeks that signify the place as much as the beautiful forests. Perhaps in another painting…

Sipsey Wilderness is a part of Bankhead National Forest, maintained by the Forest Service. WildSouth is a non-profit organization that works to restore and protect the Sipsey Wilderness and other Southern ecosystems. For more information go to wildsouth.org.

2008, 39” x 48”

Working for Peanuts: Tuskegee Institute

I learned about Tuskegee Institute in elementary school, but did not grasp the inspiring story behind the place until my first visit there: two men spent their lives dedicated to the betterment of their people and their region.

The most striking thing about Tuskegee Institute, at first glance, is the buildings that make up the campus. I was overwhelmed by all the gorgeous, rich, red brick and white trim buildings in different architectural styles. I learned that the students and faculty made the brick from Alabama clay and built many of the buildings themselves.

Booker T. Washington, a former slave, came to Tuskegee in 1881 as its first principal. He was only 25 and spent the rest of his life dedicated to the school. He believed self-sufficiency should be learned along with a scholarly education, and students had to learn practical skills that they could take back to their communities, such as farming, carpentry, bricklaying, and other trades.

In 1896 George Washington Carver was hired as an instructor in the agriculture department. I was so inspired by a film about him (shown at the George Washington Carver Museum on campus) I nick-named him the Mother Teresa of the South. Much more than a school teacher, he was a passionate, eccentric scientist, artist, and humanitarian. He taught progressive farming methods and even made “house calls” to farmers around the South with his Movable School—a horse-pulled wagon equipped for training. Even into old age he refused money and accolades in order to stay connected to his people.

The peanut in the center of the painting is the symbol that everyone associates with Carver. Among his many other accomplishments, he revolutionized farming and economics in the South by spreading the word about this easy, profitable, nutritious crop.

Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site is maintained by the National Park Service, a division of the Department of the Interior. For more information, go to www.nps.gov.

2008, 45” x 48”

The Carnivores: Splinter Hill Bog Preserve

Now owned by the Nature Conservancy, the Splinter Hill Bog Preserve is home to some of the largest and most beautiful pitcher plant bogs in the world. The site is located in the headwaters of the Perdido River, in the low hills of the East Gulf Coastal Plain in South Alabama. Not your ordinary wildflower meadow, the open fields blanketed with white, red and green pitcher plants also host a dozen other carnivorous plant species.

In order to survive in the low nutrient soil some of the plants must resort to eating insects. The pitcher plant is large enough that the skeletons of small frogs and birds have even been found inside its trumpet-like leaves. Other meat-eating plants are covered with gooey dew-like drops to which insects stick and are digested. Many unusual and rare plants grow in the bog, and along with more common varieties, can add up to 60 species in one square yard.

In order for this weird and exotic landscape to thrive, it must be set on fire at about the same frequency that Mother Nature would set it ablaze with lightening: about three times a decade. Prescribed burns maintain habitat for fire-adapted species, restore nutrients to the soil, and help prevent large wildfires. The Splinter Hill site has been systematically burned with nature’s regularity since the time of the Indians, because the locals have endeavored to preserve the pitcher plant for medicinal purposes or to sell. Now it is the Nature Conservancy’s task to burn periodically. Interestingly, maintaining the site with prescribed burns is expensive. Legal and insurance costs are quite high, to protect adjoining privately-owned properties.

I toured the bog with a group headed by Bill Finch, Conservation Director for the Nature Conservancy. I wouldn’t have noticed all the smaller carnivorous plants and learned about the various species and hybrids of pitcher plants without his expertise. He knew where to find the one, tiny, rare orchid in acres and acres of fields, pointed out the holes of the endangered gopher tortoise, and taught us how to tell the native long-leaf pine from the common slash pine, among many other things. But I knew from the beginning that among all the striking and bizarre sights I was taking in, the glamorous pitcher plant would take center stage in my painting. I’d previously marveled at them at the plant nurseries in Birmingham, but here there were thousands of them, growing literally like weeds—lovely and strange, and all over the place.

The Nature Conservancy owns and maintains Splinter Hill Bog. For more information, see www.nature.org.

2008

45” x 48”

2009, 48” x 45”

Bounty: Jones Valley Urban Farm

This painting is a tribute to all Alabama small, sustainable farms. I buy fresh food from local farmers whenever possible, and believe this practice to be important for the future of me and my family, our community, and our planet. Sustainability refers to farms that are healthy for the environment, can support themselves financially, and are socially conscientious.

I chose Jones Valley as the representative farm for this painting because it thrives in busy downtown Birmingham, setting a good example of healthy farm practices to many who normally don’t get out in the country or aren’t exposed to the benefits of fresh, organic food. Jones Valley is a non-profit organization that provides outreach programs for students and the local neighborhoods, teaching people first-hand where their food comes from, how to grow it, how it is prepared, and how it tastes. Small garden plots are offered to nearby residents, and money is raised through donations and by selling produce and flowers at local farmer’s markets.

My painting, Bounty, unfolded in an unexpected way. The title came first; I’m originally from Colorado, and after living in Alabama for 15 years, I am still amazed at how many and how well plants grow in Alabama. The several different patterns throughout the piece came about as I attempted to find abstractions of the idea of plenty. I began with botanicals and emerged with a rather kitchen-like appearance, appropriate because my connection with farms and food is most often celebrated in the kitchen.

The background of the center piece uses imagery that reminds me of an opulent palace—a version of abundance—where tiny fruit, veggies, and flowers are displayed on pedestals. Sunflowers are the most eye-popping element of Jones Valley, and I chose to reveal the back side of the flower because I found it visually interesting and a fitting symbol of the unusual urban nature of Jones Valley. The tiles are made from molds of vegetables from my own garden, Jones Valley Urban Farm, and other small local farms. The little farm landscapes are taken from small farms throughout Alabama, and are framed in the aforementioned fancy patterns. The outside of the piece continues and expands the general idea of bounty.

More information on Jones Valley Urban Farm can be found at www.jonesvalleyteachingfarm.org. Also, the Alabama Sustainable Farmer’s Network educates and supports sustainable farming.

2010, 45” x 48”

Bible Belt: Saint Paul’s Cathedral

When I first moved to the South, I was astounded by the abundance of Christian churches. I learned that Alabama has a church for every 360 people, more than double the national average. Anyone living in Alabama is well aware of the prominence of religion in everyday life, and representing it in my series seemed a must. I explored many churches in Birmingham in my first years in the state, and found them all lovely. I labored over the choice of which church to feature in my piece, wondering whether to make my decision based on political, religious, or historical reasons. Ultimately, I chose to be as non-confrontational as I could. I chose Saint Paul’s because it is my church.

Founded in 1871, the same year as Birmingham, Saint Paul’s was the city’s first Roman Catholic Church. Its face has changed over the past century and a quarter, but renovations in the past 20 years have rendered it one of the most beautiful and revered buildings in the city.

Saint Paul’s interior splendor is known not just for its plentiful arches, carved reliefs, and ornamental moulding, but for its exuberant color. The centerpiece of my painting is the Easter Lily, a universal Christian symbol of resurrection. The representations of statues come from all over the church, and I chose to paint the parts that generally remind of me of Christian symbols. The tiles were inspired by motifs found in the fantastic stained glass windows. The outside border of the piece is a simplification of the walls and dome of the cathedral, with parts of the Stations of the Cross at the bottom. Complicated pictorial narratives fill the Cathedral and are what make it magnificent. However, in the interest of keeping the imagery from getting out of hand, I chose to depict only details of most of it.

Saint Paul’s Cathedral is supported by its parishioners and by the Diocese of Birmingham in Alabama.